Why I Stopped Writing Book Reviews

...and why I'm starting back up again.

A few years ago I realised that I didn’t know what reviews were actually for. In an attempt to remedy that, I downloaded three magazines: The London Review of Books, The New York Review of Books, and The NYT Book Review. As I read through some of the entries I found that the general gist went something like this:

Tell half a story, get the reader hooked so they want to hear more.

Critique elements of the book so the reader views you as nuanced and unbiased, but choose elements that will not insult the author or their capabilities.

Write as though the reader really should be interested in this book and if they’re not, they’re inferior.

I swiftly decided that this approach to book reviews would never work for me. I’m not interested in perpetuating the mythological canon of books that everyone should read, and I don’t want to review or recommend a book just because I feel that I should.

Since I made that decision I’ve written a number of reviews that I’m really happy with, but about six months ago, I decided it was about time to re-evaluate my reason for writing reviews. Initially I assumed that this would be a quick process and that I’d start up again within a few weeks, but as the months rolled on I kept coming back to the same question.

“What’s the Point?”

Early on in my writing journey I made a point of asking that question as often as I could.

“What’s the point of this article?”

“What’s the point of reading that book?”

“What’s the point of writing?”

During my review of my reviews, however, this led me to ask a much more fundamental question. “What’s the point of reading…at all?”

I’m a voracious reader—not to mention a writer—who deeply believes in the benefit of reading not just for building up knowledge, but also for the enjoyment it can bring, and most importantly the wisdom that one can gain from the practice. I’m not convinced, however, that this is the norm, even among readers like myself. I’ve met so many people of all reading speeds and proficiencies who cannot remember what they gained from their most “beloved” books, and can’t explain why they read them beyond the book’s perceived popularity.

Whenever someone tells me, “you should read _____!” I always ask “Why?” and the vast majority of the time, I receive no answer. I want to make sure that when I recommend a book, I’m giving you, the reader, not only a solid reason for doing so, but also a roadmap for how to get the most out of that book, with the aim that you will be more equipped for the road ahead by doing so—aside from those rare occasions that I write a review about a book that I don’t recommend.

Side Note: I do think there’s space to just read a novel for enjoyment, and sometimes we read books that don’t end up being as beneficial as we thought, but we should always gain something from reading anything.

So why return to writing reviews? Well, I’ve spent the last six months or so researching for a book proposal about the intersection of reading and the acquisition of wisdom. I have much more to learn, but I feel like I’ve gotten to a place now where I can better identify where books sit along the spectrum of reading difficulty, and then marry that with helpful guidance about how to read for wisdom’s sake. Today I’m gonna provide a simple guide for how anyone can grow in wisdom, whether reading books, articles, tweets, or anything else! This will form the basis for every review you’ll read for the foreseeable future, and I have some amazing books to share with you.

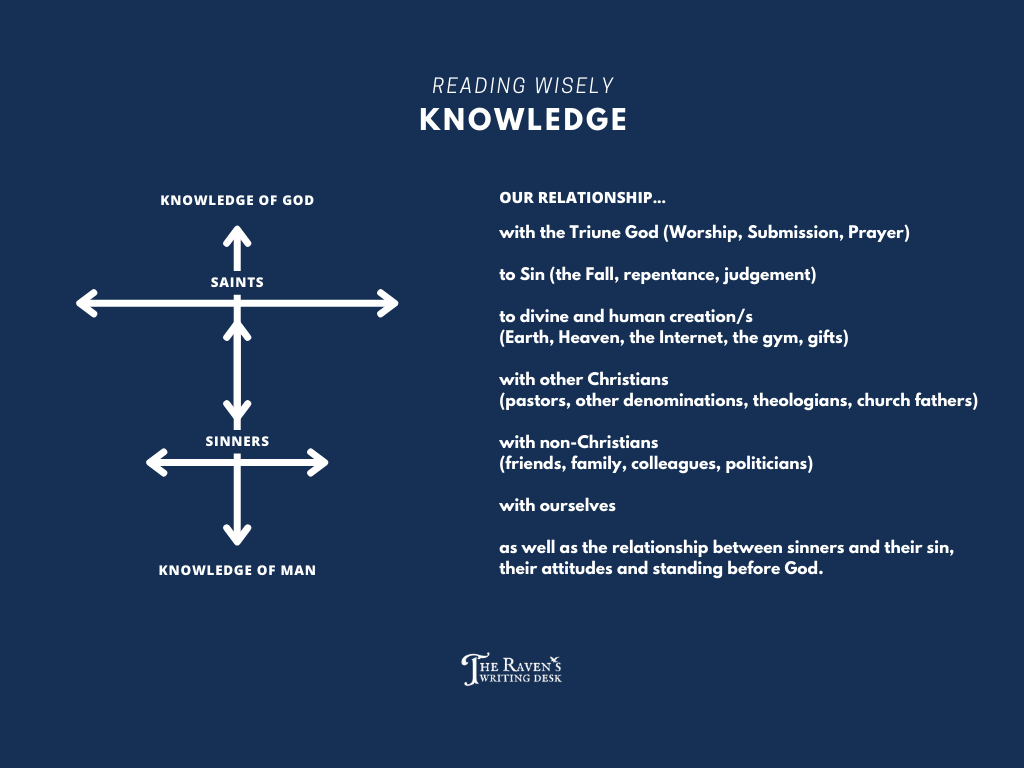

Knowledge of God and the Knowledge of Man

The Bible tells us over and again to seek out wisdom…but where should we be looking? In my life the two primary means of acquiring wisdom have been suffering, and literature. Just as I’ve learned patience both through stubbed toes and slipped discs, the acquisition of wisdom through reading isn’t relegated to those who can read the most thickly-dusted tomes. Whenever a friend of ours has a baby and they ask for books as a gift, we give them a volume from the FatCat series from Lexham Press, why? There are two reasons, firstly so they can teach their child wisdom by doing so, but also because part of the vision for that series is to help train parents in how to catechise their children well; you can hear more about that here. Many picture books contain fewer words total than there are in this paragraph alone, and yet, they can be an amazing tool, so whatever your “reading level” know that you’re already well equipped to start on this journey.

I want to suggest that you need to look for two things when you’re reading to keep wisdom front and centre. John Calvin puts it like this:

“Nearly all the wisdom we possess, that is to say, true and sound wisdom, consists of two parts: the knowledge of God and of ourselves.”1

Put simply, the knowledge of God and the knowledge of man.

The most simple form of ‘literature’ I can think of is a text message.

Here’s an example of of a recent message I received:

“Surprise, surprise, the anticipation was worse than the actual thing!”

Before I say anything else, this isn’t an academic endeavour. I’m not going to encourage you to spend an inordinate amount of time analysing even the most basic messages, but I think there’s a benefit of taking for a second to think about what this tells you about the sender, in order to get more out of other literature.

So, what do you know?

They were anticipating difficulty; they are now being blessed; they are recognising their previous misevaluation, and even noticing a habit, perhaps?

What might it tell you about God? Or what would you say to this person about what you already know about God in response? I’ll leave this one to you.

Every piece of writing, whether Christian or secular can tell us something about God or about man—even if it’s only about a specific person. Wisdom then flows from acting upon that knowledge relationally.

It looks something like this:

As Christians our wisdom should lead us to act wisely, to walk humbly, to speak in accordance with what we know about God and about man. James says this:

Who is wise and understanding among you? By his good conduct let him show his works in the meekness of wisdom…But the wisdom from above is first pure, then peaceable, gentle, open to reason, full of mercy and good fruits, impartial and sincere. And a harvest of righteousness is sown in peace by those who make peace.

James 3:16,18 ESV

So, when you’re reading, you should have these questions in mind:

What does this tell me about God? (Either God himself, or a secular view of God)

What does this tell me about man? (Mankind; Men and Women; Families etc)

What if that doesn’t apply to the book I’m reading?

Short answer: It does.

A few years ago I had a conversation with my cousin. She’s a very accomplished doctor now but at the time she was still studying. Throughout that journey she’d met a number of former patients who were devastated following surgery by the condition of their scars. There was nothing physically wrong with them, the scars weren’t painful, or causing any health issues, but they were aesthetically unattractive and were causing the patients serious mental strife. When she raised this with surgeons, the response she received was telling. “It’s just a job, we can’t care about that during the procedure.”

The surgeons brought a lifetime of experience, as well as a significant amount of knowledge about the human body, but nothing of the human condition, or wisdom about how to apply the knowledge they possessed for the ongoing ramifications of their work. My cousin saw people, the surgeons saw patients.

No matter which book you’re reading, area you’re studying for, or tweet you’re about to reply to, knowledge of God and knowledge of man are intrinsically applicable.

Keeping asking those questions, even when answers are hard to find.

Praticals

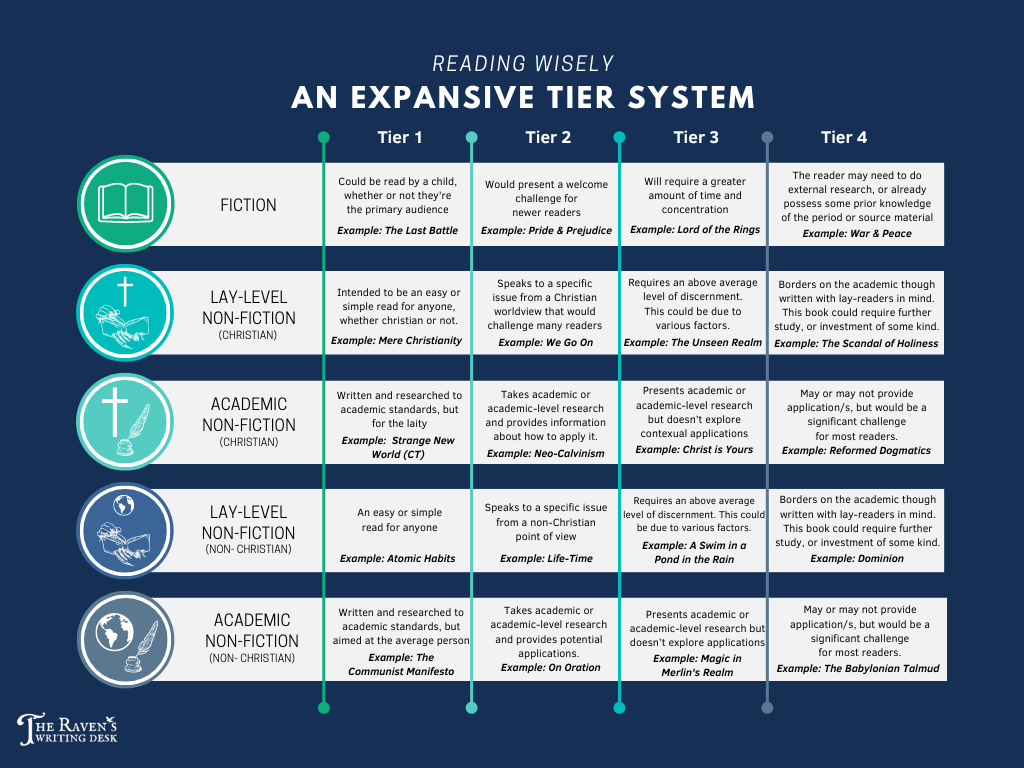

I believe that you can start on this journey of reading wisely for wisdom’s sake regardless of your perceived reading level, however, this assumes that you know whereabouts you sit on that spectrum. I picked up a book recently having been encouraged to do so for a book club, and quickly found out that the target audience was teenage girls between the ages of about 11-15. I don’t have any issue what that, necessarily, but I had been expecting something written for adults; possibly even for academics. As you can imagine, the experience was rather jolting.

In order to do my best to make sure this doesn’t happen to you, I’ve put together an expansive tier system, to help you decided whether any book I recommend is right for you. I’ll link this in every review I write, so there’s no need to keep referring back, but if you read a review and think, “that sounds interesting, but what does reading this book entail?” I hope this will be of help.

I’d love to hear which books you would have included in this system, and which books you would love to see me review.

That’s all for today, if you’ve made it this far, please give this article a like and a comment, you have no idea how much it helps.

Grace and Peace,

Adsum Try Ravenhill

Recommended Articles from around the Web:

Eliza from More by Reaping began an excellent exploration of the true villain in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. This piece was well-researched and crafted, and yet took the time to add humour and levity. I laughed and nodded heartily throughout:

If you haven’t been keeping up with Karen Swallow Prior‘s journey through Shakespeare’s sonnets, I highly recommend you start with this one:

The Polycarp Series So Far

This series on Polycarp’s letter to the Philippians was born out of a shared love that Tim and I have for the early church, but also a love for the church in our time. We believe that this letter has so much to teach us still, not least because Polycarp isn’t afraid to challenge us. Each of these articles is written in the form of a letter, either to Ti…

The Institutes of Christian Religion

I'm going to give your contact to the person who organizes book reviews for Christianity Today!

Oooh I'm excited to read your book reviews again, I've missed them!